The Maccabees, Martyrs, and the Messiah

How the Hanukkah story inspired Jewish theology that explains how Jesus’ death atones for the sin of the world

This article is based on “The Maccabees, Martyrs, and the Messiah,” an audio teaching by the Rev. Aaron Eime. Listen or read below.

Hanukkah is not quite a biblical holiday, yet it has become a very visible Jewish holiday around the world . The events th at Hanukkah commemorates are recorded in the four Books of the Maccabees, none of which enter either the Jewish or Protestant Christian canons. [1]

Yet, Hanukkah gets a mention in the New Testament. John 10:22-23 records Jesus walking in the temple during the winter Feast of Dedication . Hanukkah means “ dedication,” and it was the Maccabees who rededicated the temple in the winter after the desecration by Antiochus Epiphanies (1 Macc 4:52- 9). [2]

Jesus celebrated Hanukkah, and if we are imitators of the Messiah, it must be all right for us to light candles and eat doughnuts and latkes. The holiday should also draw us into study, as some of the theological questions and answers that arise from the Maccabean period informed how the New Testament writers understood the person and work of Jesus as the Messiah of Israel and the Savior of the world.

Restoration interrupted

In 586 B.C., Judah was conquered by Nebuchadnezzar and exiled to Babylon. The prophets are clear: Judah, and Israel before her, suffered for their sins. Then the captivity ends. Cyrus, ruler of the Persian empire, allows the exiles to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the temple. The restoration of the kingdom was on the way.

More than 300 years later, the Seleucid empire tried to make the Jews into Greeks by force, outlawing Sabbath observance, circumcision, and the reading of the Torah. The Greeks went so far as to sacrifice a pig on the altar in Jerusalem.

A revolt was led by a priest named Mattathias the Hasmonean and his sons starting in 167 B.C. They were victorious and reclaimed the temple for God, rededicating it on the 25th of Kislev (1 Macc 4:52). The Hasmoneans, who called themselves the Maccabees — that is, the Hammers — ruled restored Israel for about one hundred years. (If you’re wondering when the miracle of the oil happened, no such miracle is recorded in the four books of the Maccabees. The story of the oil only appears in the Talmud 600 years later.)

The Maccabees believed that they were bringing about the final redemption of Israel. Assuming they were living in the messianic age, they expanded Jewish territory by force, converting those around them. They also changed how the priestly succession worked in the temple, leading to the temple corruption depicted in the Gospels. The Hasmonean Dynasty eventually descended into civil war, leading to Rome’s conquest of Jerusalem in 63 B.C.

Why do the righteous suffer?

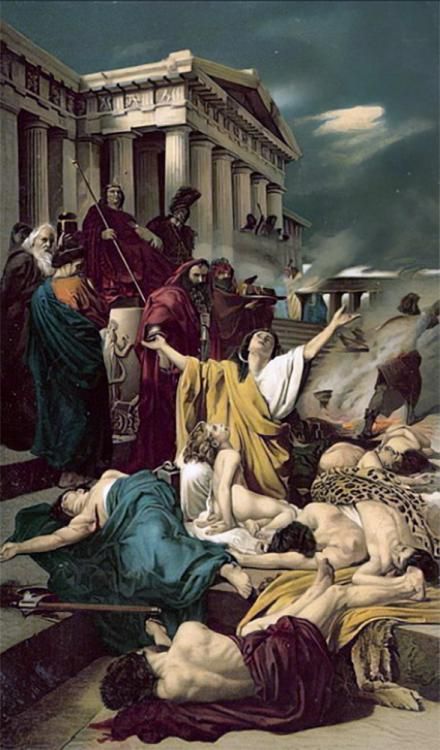

The Hellenizing Seleucids killed many pious Jews who would not give up their devotion to God. One example recorded in 2 Maccabees 7 is a story of a woman and her seven sons murdered for refusing to eat pork. The theologians begin to ask:

- Is it worth dying for faith?

- Does martyrdom have any effect?

- Why does a good, all-powerful God allow his faithful followers to suffer and die?

They conclude that the martyrs’ death s served as a ransom for the sin of Israel: “Through the blood of those devout ones and their death as an expiation, divine Providence preserved Israel that previously had been afflicted” (4 Macc 17:21-22). The blood of pious martyrs becomes an atoning sacrifice for Israel (4 Macc 17:5, 12).

Better than the blood of Abel

Having arrived at this theological truth, late Second Temple period scholars went back into the Scriptures to look for martyrs. The first martyr is Abel, who offers God a pleasing sacrifice and is then murdered by his brother Cain (Gen 4) . A tradition develop s that when one dies , Abel is the first to judge all souls . This first martyr, still bleeding, would sprinkle his blood on those entering the presence of God. The righteous would be able to continue but the evil would not.

When Jesus of Nazareth appears and announces himself as the Messiah, his countrymen are chafing under Rome’s oppressive yoke. To many first-century Jews, Rome must have appeared as the Seleucids returned. Rome had absorbed Hellenistic culture and now imposed their rule through out the Mediterranean world. The people of Judea , Samaria and Galilee desired a Maccabean-like m essiah who would overthrow Rome and reestablish Israelite independence.

Instead, Jesus redeems Israel by suffering like Abel and the righteous who were murdered by the oppressive Greeks. Jesus, a pious Jew, was betrayed by the corrupt leadership initiated by the Hasmoneans and martyred by pagan Rome. By Second Temple theology, his blood qualifies to have atoning effects for the sins of Israel.

However, Jesus is no ordinary martyr. He is the Word of God, the essence of God made flesh (John 1:1, 14). The atoning power is magnified to include all the earth and all the nations and even cleanses the temple in heaven (Heb 9:23-24). Thus, the writer of Hebrew s declares that Jesus’ sprinkled blood speaks more graciously than the blood of Abel (Heb 12:24).

This article is based on “The Maccabees, Martyrs, and the Messiah,” an audio teaching by the Rev. Aaron Eime. Aaron Eime served as the deacon at Christ Church Jerusalem and teacher for CMJ Israel for many years. He is now the director of CMJ UK and lives with his wife and children in England.

Footnotes

- The first two books of the Maccabees are in the Roman Catholic canon , and all four are in Eastern Orthodox canon.

- Solomon’s Temple was dedicated during Sukkot (1 Kgs 8:2, 2 Chron 5:3), and the second temple was initially dedicated in the month of Adar in early spring (Ezra 6:15-16).

Blessed by this post? Ready to sow into the work of CMJ? No gift is too small. we are blessed by your partnership.